THE ROOFING SLATES OF DINORWIC [DINORWIG].

700 ACRES OF QUARRY.

THOUSANDS of holiday visitors every year coach round Snowdon from Carnarvon [Caernarfon],

and gaze with astonishment at the terraced precipices of Elidir, opposite

Llanberis. Very few, however, realise the full significance of the mighty

Dinorwic [Dinorwig] or Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] slate quarry which has carved

its way into the mountain side.

THOUSANDS of holiday visitors every year coach round Snowdon from Carnarvon [Caernarfon],

and gaze with astonishment at the terraced precipices of Elidir, opposite

Llanberis. Very few, however, realise the full significance of the mighty

Dinorwic [Dinorwig] or Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] slate quarry which has carved

its way into the mountain side.

Yet this quarry is famous the world over for the slate which it produces.

No form of economy is more delusive, or more expensive in the long run, than

to roof a house with inferior material, however cheap in the beginning.

Fortunately, Nature herself has provided an ideal material for the

purpose-namely, slate. This stone has been hardened for centuries in the solid

earth by incalculable pressure, which has rendered it extraordinarily hard-far

harder than any substance, like brick or pottery, which can be produced

artificially by the action of fire in kilns. Geologically slate belongs to fie

oldest systems in the Primary division-pre-Cambrian, Cambrian, Ordovician, and

so forth-and is thus among the oldest stones in existence. Its age is shown by

the fact that it contains no fossils. Moreover, unlike all other stone, it is

capable of being split longitudinally into smooth, flat layers, each of which

retains the hardness of the original blocks.

WELSH SLATE THE BEST

There is no slate in the world which possesses the quality of hardness in so

high a degree as that of Wales. If corroboration were required, it might be

found in the significant fact that geologists have given to the oldest and

hardest of slate the adjective Cambrian, Cambria being the ancient Roman name of

Wales. It is in the north-west corner of Wales that the best slate is found. The

observant traveller between Bangor and Carnarvon [Caernarfon], as he passes

along the Menai Straits, will see everywhere slate in practical use, not only

for roofs, but for nag-stones, boundary walls, gravestones, doorsteps, and the

like. Half-way in the journey he will come to the small town of Port Dinorwic [Y

Felinheli], which has come into existence as a harbour for the great slate

quarry.

QUALITY OF DINORWIC [DINORWIG] SLATE.

Just as slate stands pre-eminent among roof materials, so Dinorwic [Dinorwig]

slate is unsurpassed throughout the world in the excellence of its quality. The

quarry is the largest in the world, and its slate is the hardest and most

durable. It has every possible colour - blueish, reddish, grey, sea-green,

&c.- and the various qualities (e.g., Best and Seconds Old Quarry, Best and

Seconds New Quarry, Best and Seconds Green and Wrinkled, Best and Seconds

Mottled, etc., etc ) simply cannot wear out. Quite recently a Blackburn slater

stripped the roof from a house which was known to have stood unaltered for a

hundred years. Dinorwic [Dinorwig] slate had been used, and he found that they

were absolutely as good as new. They were immediately used for another

horse-which also they will assuredly outlast.

This intense hardness is due partly to the tremendous natural pressure which

has acted for countless centuries upon the lowest rock-strata and partly also to

the bands of igneous rock which have been forced up through the slate beds.

Obviously the intense heat of these volcanic neighbours has submitted the slate

to an ordeal to which ordinary heat is a mere nothing. Another important

advantage is that the slate is absolutely impervious to the corrosive action of

acids in the atmosphere. An example of this is the fact that the largest glass

manufacturers in the world, Messrs. Pilkington, of St. Helens, have found it

absolutely necessary to roof their works with Dinorwic [Dinorwig] slate. No

other material can withstand the gases which are generated by glass-working, and

the many chemical manufactories in the town. Yet Dinorwic [Dinorwig] or Port

Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] slate, as it is also called, withstands this severe

strain with complete equanimity.

This intense hardness is due partly to the tremendous natural pressure which

has acted for countless centuries upon the lowest rock-strata and partly also to

the bands of igneous rock which have been forced up through the slate beds.

Obviously the intense heat of these volcanic neighbours has submitted the slate

to an ordeal to which ordinary heat is a mere nothing. Another important

advantage is that the slate is absolutely impervious to the corrosive action of

acids in the atmosphere. An example of this is the fact that the largest glass

manufacturers in the world, Messrs. Pilkington, of St. Helens, have found it

absolutely necessary to roof their works with Dinorwic [Dinorwig] slate. No

other material can withstand the gases which are generated by glass-working, and

the many chemical manufactories in the town. Yet Dinorwic [Dinorwig] or Port

Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] slate, as it is also called, withstands this severe

strain with complete equanimity.

Similarly the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board always specify Dinorwic [Dinorwig]

slate for their warehouses and sheds. the surface of Dinorwic [Dinorwig] slate

is so hard that no damp can find ingress. Tested by chemical analysis, it

emerges as the finest slate the world produces. A rough experiment emphasises

this point. If overnight you affix a ring of putty to a Dinorwic [Dinorwig]

slate, and fill the circle with water, no moisture will be found on the

underside in the morning; in the case of inferior slate the water will gradually

percolate through the pores till it readies the lower surface.

Similarly the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board always specify Dinorwic [Dinorwig]

slate for their warehouses and sheds. the surface of Dinorwic [Dinorwig] slate

is so hard that no damp can find ingress. Tested by chemical analysis, it

emerges as the finest slate the world produces. A rough experiment emphasises

this point. If overnight you affix a ring of putty to a Dinorwic [Dinorwig]

slate, and fill the circle with water, no moisture will be found on the

underside in the morning; in the case of inferior slate the water will gradually

percolate through the pores till it readies the lower surface.

THE QUARRY ITSELF.

Visitors to North Wales cannot spend a more interesting day anywhere than at

Dinorwic [Dinorwig]. The quarry itself is seven miles inland from the Menai

Straits. It is cut into the south side of the mountain called Elidir, which

overlooks the village of Llanberis, and confronts the great mass of Snowdon

across the two lakes, Peris and Padarn. It has been worked continuously for a

century and-a-half, during which millions of tons of slate have been removed.

Visitors to North Wales cannot spend a more interesting day anywhere than at

Dinorwic [Dinorwig]. The quarry itself is seven miles inland from the Menai

Straits. It is cut into the south side of the mountain called Elidir, which

overlooks the village of Llanberis, and confronts the great mass of Snowdon

across the two lakes, Peris and Padarn. It has been worked continuously for a

century and-a-half, during which millions of tons of slate have been removed.

THE DINORWIC [DINORWIG] RAILWAY SYSTEM.

When a sufficient number of slates have accumulated and are then ready for

transport, they are placed in small trucks running upon a narrow gauge railway

which ramifies into every corner of the great quarry. There are upwards of 50

miles of this railway, and thousands of trucks are used. They are hauled along

the terraces to the nearest incline by light locomotives, of which there are

some two dozen in the workings. Down the inclines-some of which have a gradient

of one in one! - there is a double line. The trucks are securely attached to an

endless steel rope with a breaking strain of nearly 30 tons which winds round

two great drums in a shelter at the top. the trucks, going down by force of

gravity, haul up "empties," and so the circle is completed. Each

gradient is complete in itself with junctions which communicate with subsidiary

terraces right and left. Viewed for a distance they give the impression of a

series of ladders, each beginning and terminating in a small level space where

the trucks are transferred from one rope to another. Each series of such

gradients ends on a sort of main line which runs the entire length of the lowest

quarry level, and communicates with what may be called the trunk line from the

quarry to the quays of Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli].

When a sufficient number of slates have accumulated and are then ready for

transport, they are placed in small trucks running upon a narrow gauge railway

which ramifies into every corner of the great quarry. There are upwards of 50

miles of this railway, and thousands of trucks are used. They are hauled along

the terraces to the nearest incline by light locomotives, of which there are

some two dozen in the workings. Down the inclines-some of which have a gradient

of one in one! - there is a double line. The trucks are securely attached to an

endless steel rope with a breaking strain of nearly 30 tons which winds round

two great drums in a shelter at the top. the trucks, going down by force of

gravity, haul up "empties," and so the circle is completed. Each

gradient is complete in itself with junctions which communicate with subsidiary

terraces right and left. Viewed for a distance they give the impression of a

series of ladders, each beginning and terminating in a small level space where

the trucks are transferred from one rope to another. Each series of such

gradients ends on a sort of main line which runs the entire length of the lowest

quarry level, and communicates with what may be called the trunk line from the

quarry to the quays of Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli].

NARROW GAUGE AND BROAD GAUGE.

The slates having arrived at the lowest level are examined, classified, and

credited to the particular quarrymen who have delivered them. At this point an

obvious problem meets with a most ingenious solution. Obviously the narrow

railway required for the gradients and tunnels of the quarry system is unsuited

to a seven-mile line on open and fairly level country. the quarry engineers have

therefore built their trunk line with a four-foot gauge, and prepared trucks

which each carry four of the smaller trucks required for quarry work. The

smaller trucks are run on their own line to the very edge of the terminus of the

trunk line, and pushed on to the larger trucks waiting at a lower level to

receive them. They are securely held in position on the larger trucks by an

automatic device. A complete train of these larger trucks, which may carry

altogether 100 tons of slate, is then dispatched to Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli]

for shipment.

UNDAUNTED ENGINEERING.

The terminus of this trunk lines is not quite the end of the journey. There

is still a quarter of a mile of very steep descent to the harbour. The small

trucks are, therefore, wheeled off the larger trucks, and once again separately

attached to an endless chain which escorts them to fit quay, where the slates

are stored close to the ships.

The terminus of this trunk lines is not quite the end of the journey. There

is still a quarter of a mile of very steep descent to the harbour. The small

trucks are, therefore, wheeled off the larger trucks, and once again separately

attached to an endless chain which escorts them to fit quay, where the slates

are stored close to the ships.

Sir Charles Assheton-Smith comes of a long line of ancestors who have held

large tracts of land in Carnarvonshire [Caernarfonshire] since the time of

Charles's II., and resides on the beautiful wooded estate of Vaynol, close to

the Menai Street and the Britannia Tubular Bridge which carries the Holyhead

line.

THE HARBOUR AND WHARVES.

Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] itself nestles in a tiny inlet opening out of the

Strait. Its old name is Velinheli, which means "Saltwater Mill," and

derives from an old mill which stood on the inlet and used the ebb and How of

the tide to turn its wheels. The inlet was lengthened and widened some ten years

ago to admit the fleet belonging to the quarry. It is entered by a lock, and

there is a dry dock for repairs. At the head is the private electric light and

power station which supplies not only the wharves, but also the village of Port

Dinorwic [Y Felinheli], which has grown out of the needs of the great quarry

enterprise. The harbour has a complete repairing equipment, in charge of a

competent engineer.

THE OVERSEAS TRAFFIC.

Day after day the steamers leave Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] carrying slates

to Liverpool and all the ports of the British Isles, especially Lancashire,

Scotland and the East Coast. From Liverpool the slates are sent all over the

world - to Germany, Austria, South America, India, Australia and the Cape. The

present writer saw a consignment of 200 tons ready for shipment to Sydney via

Liverpool. On an average some 100,000 tons annually leave the harbour of Port

Dinorwic [Y Felinheli].

Day after day the steamers leave Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] carrying slates

to Liverpool and all the ports of the British Isles, especially Lancashire,

Scotland and the East Coast. From Liverpool the slates are sent all over the

world - to Germany, Austria, South America, India, Australia and the Cape. The

present writer saw a consignment of 200 tons ready for shipment to Sydney via

Liverpool. On an average some 100,000 tons annually leave the harbour of Port

Dinorwic [Y Felinheli].

THE QUARRYMEN.

More than 3,000 men are employed in the quarry and at the harbour. Owing in

large measure to the generous interest taken in them by Sir Charles and Lady

Assheton-Smith, the relations between them are cordial in the extreme. It is

actually twenty-five years since any dispute has occurred. When we remember the

acute controversies to which industrial revolutions have given rise in that

time, this fact is sufficiently remarkable. The men grow old in the service, and

it is no uncommon thing to find a man of over seventy-five years still at work,

hale and hearty. In many cases, too, the trade is hereditary through many

generations.

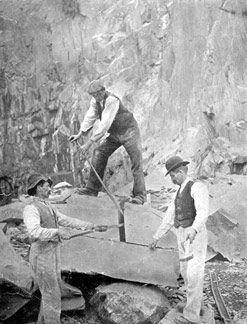

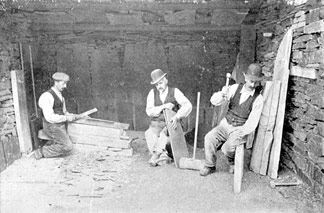

Quarrying is done and paid for by the piece. Two men join together as

"partners," and receive a definite area of rock on which to work. This

allotment is called a "bargain." It is always 21 ft long, and ranges

up to a height of 75 ft. One of the partners works at the face of the rock

blasting and preparing the rough blocks which are loosened ; the other receives

it in their common shed and finishes oft the work. The two partners hire a third

man, known as their journeyman, a youth who has served a kind of apprenticeship

of about two years. Every two weeks the slate produced from each bargain is

calculated and paid for, the partners sharing, and jointly remunerating their

journeyman. Payment is made at so much per 100 slates, according to their size,

together with a certain poundage according to the quality of the slates

produced.

Most of the men live on the proprietor's land in Llanberis, Ebenezer, and

other villages. They are conveyed to the quarry by special carriages on the

quarry line, for which they pay a nominal sum. In former days they propelled

themselves along the rail on hand-worked velocipedes, turn and turn about-a

method both hard and dangerous to health. Some 300 men have their homes in

Anglesey; for these men Sir Charles has erected barracks in which they can live

while at work for the nominal charge of one shilling per annum.

Most of the men live on the proprietor's land in Llanberis, Ebenezer, and

other villages. They are conveyed to the quarry by special carriages on the

quarry line, for which they pay a nominal sum. In former days they propelled

themselves along the rail on hand-worked velocipedes, turn and turn about-a

method both hard and dangerous to health. Some 300 men have their homes in

Anglesey; for these men Sir Charles has erected barracks in which they can live

while at work for the nominal charge of one shilling per annum.

Hours are from 7 a.m. to 5.30 in summer, and in winter from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.,

with an hour for dinner, but the blasting intervals add up to a considerable

further period of rest. There are 23 working days in each month, the Saturdays

following the monthly pay-days being free. Other recognised holidays are Good

Friday, Easter Saturday, Easter Monday, Whit Monday, Harvest Festival, and

Christmas Day.

Serious accidents are remarkably few, and the majority of accidents which

occur are of the nature of small cuts and bruises from splinters of rocks. Sir

Charles Assheton-Smith provides a completely furnished hospital, which is free

to all his employees. There is a highly-qualified surgeon with a staff of

nurses, but it is satisfactory to learn that the in-patients are practically

never numerous enough to occupy the whole accommodation. There are nearly a

hundred pensions of £13 per annum, which are allocated to the deserving cases

as they fall vacant. But the work and the climate are so healthy, the men so

thrifty and contented in the mass, that both pensions and hospital are more than

adequate.

Serious accidents are remarkably few, and the majority of accidents which

occur are of the nature of small cuts and bruises from splinters of rocks. Sir

Charles Assheton-Smith provides a completely furnished hospital, which is free

to all his employees. There is a highly-qualified surgeon with a staff of

nurses, but it is satisfactory to learn that the in-patients are practically

never numerous enough to occupy the whole accommodation. There are nearly a

hundred pensions of £13 per annum, which are allocated to the deserving cases

as they fall vacant. But the work and the climate are so healthy, the men so

thrifty and contented in the mass, that both pensions and hospital are more than

adequate.

The whole face of Elidir mountain is carved into terraces connected by steep

gradients, which give access from the lake level to the topmost workings, some

1,800 feet above the lake. Not even the purist in literary style could gainsay

the propriety of describing the quarry as colossal. As the visitor is conveyed

by the light railway round the base of the mountain, cutting after cutting,

precipice after precipice comes into his view. Cavernous recesses cut into the

heart of the rock, and an apparently endless series of terraces scar the grey

background of the hillside.

Even from the vantage ground of a terrace half-way up the quarry the highest

workings are out of sight ; from no spot can one see all the cuttings which have

been quarried into the wide curve of the mountain side. The total area of the

workings is no less than seven hundred acres.

The story of the slate from the moment of its removal from the solid rock to

its shipment in one of the quarry's steamers at Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] is

one of absorbing interest The first step is to blast the rock and detach

fragments of suitable size for working. This blasting requires great skill and

experience. If the explosion is too violent the slate will be shivered to atoms:

the charge must be carefully calculated and inserted in such a way as to detach

the required portion. The hole into which the charge is inserted is made by a

rod called a rock-drill, worked by steam or by compressed air, and capable of

drilling a hole seven yards deep.

The story of the slate from the moment of its removal from the solid rock to

its shipment in one of the quarry's steamers at Port Dinorwic [Y Felinheli] is

one of absorbing interest The first step is to blast the rock and detach

fragments of suitable size for working. This blasting requires great skill and

experience. If the explosion is too violent the slate will be shivered to atoms:

the charge must be carefully calculated and inserted in such a way as to detach

the required portion. The hole into which the charge is inserted is made by a

rod called a rock-drill, worked by steam or by compressed air, and capable of

drilling a hole seven yards deep.

BLASTING PRECAUTIONS.

Rigid regulations govern the blasting operations. They must be carried out at

fixed times and simultaneously at all the workings. At the appointed hour a

steam whistle sounds so as to be audible all over the quarry. Immediately all

the men, except those who are to fire the trains of powder, retire to specially

constructed shelters, which are absolutely proof against any rock which might be

shot into the air. At a second signal the fuses are fired, and the remaining men

join their comrades. A period of profound silence ensues, and then all the

quarry booms and thunders with a series of explosions. Five minutes after the

whistle blows again, and the men return to work on the detached masses of slate.

Each party is required to watch its own blast; and should any charge have failed

to explode, a signal is given, and all men in the vicinity are ordered to remain

in shelter for a full half-hour. If is frequently necessary to blast away

outcrops of useless rock, such as granite. Then more powerful explosives are

used, such as dynamite and nitro-glycerine. Of gunpowder alone the almost

incredible quantity of 90 tons is used annually in ordinary blasting.

SPLITTING AND TRIMMING.

Two processes are followed in working the rough blocks of slate-one by

machinery, one by hand. the finest qualities are so amazingly hard that

machinery is useless; no saw would be strong enough and the edges of the stone

would be chipped and splintered. Hence such slates are worked by hand with a

chisel and hammer. There is something almost uncanny in the way in which the

slates are split into layers of required thickness. The chisel is placed at any

point in the edge of the slate, and after one or two light taps of the hammer,

an even crack appears. the two layers are then gently pressed apart with their

new surfaces absolutely smooth and even. It is actually possible to divide thus

a slab one inch thick into sixteen separate slates. In practice, however, no

slates are made less than 1/6 inch thick. The quarryman's skill consists in

splitting in such a way as to avoid waste and to make the slates as large as

possible up to an ordinary maximum of 24 inches by 14.

Two processes are followed in working the rough blocks of slate-one by

machinery, one by hand. the finest qualities are so amazingly hard that

machinery is useless; no saw would be strong enough and the edges of the stone

would be chipped and splintered. Hence such slates are worked by hand with a

chisel and hammer. There is something almost uncanny in the way in which the

slates are split into layers of required thickness. The chisel is placed at any

point in the edge of the slate, and after one or two light taps of the hammer,

an even crack appears. the two layers are then gently pressed apart with their

new surfaces absolutely smooth and even. It is actually possible to divide thus

a slab one inch thick into sixteen separate slates. In practice, however, no

slates are made less than 1/6 inch thick. The quarryman's skill consists in

splitting in such a way as to avoid waste and to make the slates as large as

possible up to an ordinary maximum of 24 inches by 14.

The trimming is done by placing the slate upon a sharp edge, and breaking off

protuberances by short, sharp strokes with a kind of knife blade.

Cutting by machinery is a more economical method in the case of suitable

material. For this purpose circular saws are used. the work is accomplished with

greater accuracy and considerably less wastage. About half-way up the quarry

there is a large shed which contains some thirty of these saws driven by a

60-horse-power motor. For this and two other similar motors the power is

obtained from the North Wales Electric Power Company. Three wires carry a 10,000

volt current to the quarry, where it is reduced to 500 volts and distributed

round the upper parts of the workings, where water power is not attainable.

Source: Slate Trades Journal, December 1912