The

History of Quarrying - The Slate

Industry of Ffestiniog

THE

SLATE INDUSTRY

OF

FESTINOG

(N. Wales)

With the Compliments of

The Associated Slate Quarries

The Slate Industry

of North Wales

The Festiniog Slate Quarries

|

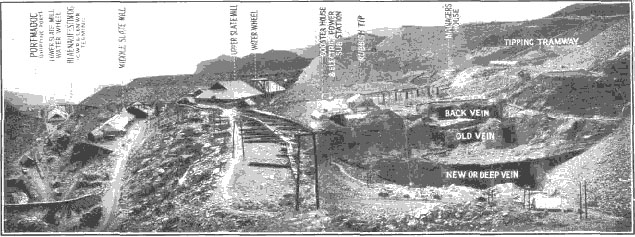

| Composite bird's-eye

view of a Festiniog Slate Quarry

(diagrammatic section), showing

order of slate veins. |

Although commonly spoken of as "slate quarries," the

Festiniog [Ffestiniog] group in

Merionethshire are actually slate mines

worked on the underground principle of

alternate openings, locally termed chambers,

and walls or supporting pillars of solid

slate. In this they differ from their sister

workings in Caernarvonshire, which are

mostly of the open kind and consist of a

series of terraced steps ; somewhat

analogous in lay-out to the old Roman

amphitheatres.

The dip of the slate veins at Festiniog [Ffestiniog],

at an average of 30° from the horizontal,

in hilly country, necessitates the winning

of the slate rock by burrowing below the

surface in order to follow the course of the

slate-producing strata, and some of the

lowest workings are as much as 1,500 ft. or

more down. As will be readily understood,

the outlay in driving the adits, or as is

more usual to-day, in sinking inclines on

the angle of dip of the slate vein, and

horizontal levels at 50 to 60 ft. vertical

intervals, from which to open out the

chambers where the slate blocks are

produced, together with the accompanying

cost of haulage, compressed air equipment

for drilling, and pumping to keep the

workings clear of water, is very great.

There are advantages and disadvantages in

underground quarrying as compared with open

working. On the one hand, the open slate

quarries are liable to stoppage or to having

their operations slowed down in bad weather

by snow, frost and rain, and suffer from the

necessity to remove heavy " overburden

" ; on the other hand, having once

removed the overburden, they are able to win

100 per cent. of the slate rock. Whereas, in

the Festiniog [Ffestiniog] slate mines one must have 40

per cent. to 50 per cent. of exploitable

slate ungotten in the pillars supporting the

mine, though, to counterbalance this the

total tonnage mined is very much less for

every ton of actual slate produced, and

inferior rock need not always be removed.

THE SLATE-BEARING

STRATA

The slate-bearing strata of Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

belong

to the Ordovician or Lower Silurian systems,

and are of an uniform soft blue-grey colour,

although the North Vein or topmost bed shows

a tendency to be slightly darker. The

chemical analysis of a standard Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

slate shows silica 55 per cent., alumina 25

per cent., iron oxide 11 per cent., the

remainder being composed of various elements

of which the chief is magnesia. The lime

contents - an excess of which often

characterises an inferior slate - are

negligible.

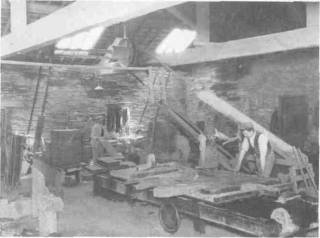

|

| Entrance to underground

workings, showing slate chamber and

pillar left in position to support the

superimposed mountain. |

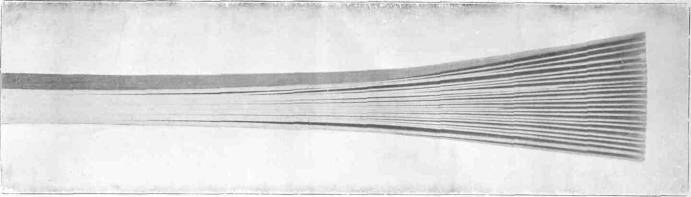

The finely-developed cleavage allows the

slate rock to be split into amazingly thin

laminae by hand-for instance, a strip only

1/6 ins. thick can be split into 26 strips, a

remarkable tour de force and example of

extreme manual craftman-ship. A unique

feature of Festiniog [Ffestiniog] slate is its

resilience, which permits of one of these

strips 3 ft. long or more, only 1/20-in.

thick, being bent this way and that as a

similar strip of steel. Indeed, if it were

possible to obtain delicate enough tools,

the slate rock could be split even thinner.

Clever quarrymen make fans out of a solid

piece of rock, beautifully turned out in

fretwork designs, capable of opening and

shutting like the real article. Such

properties yield a roofing slate of unique

elasticity and strength, and it is the

possession of these two qualities, combined

with chemical inertness and its inability to

absorb moisture, which enables the Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

slate to yield a roofing material of ample

strength and great durability when split to

a thickness of no more than 1/6 in. This is

borne out by the following figures, the

result of a number of tests :-

Tensile strength, 8,470

Ibs. per sq. in.

Resistance to compression, 31,431 Ibs.

per sq. in. ; |

and a Festiniog [Ffestiniog] slate, 12 ins. wide, 1/6

in. thick, placed on supports 22 ins. apart,

load applied at centre, yielded :-

Mean ultimate load, 166

Ib. ;

Mean maximum deflection, .54 in |

A Festiniog [Ffestiniog] slate is also

practically non-absorbent, as, after being

dried and then immersed for 24 hours, showed

the remarkably low figure of 0.016 per cent.

absorption by weight.

The several slate deposits worked at Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

are of considerable thickness,

often from 150 ft. up to as much as 300 ft.,

measured on the horizontal, inter-stratified

with beds of chert and other rocks of

superior hardness to the workable slate.

These slate veins or beds are known in their

ascending order as the New or Deep Vein, the

Old Vein, Back or Middle Vein, and North

Vein. In addition, there is the Manod Vein

under the New or Deep Vein again, but this,

at present, is only being worked to quite a

small extent.

|

| Quarrymen drilling

underground on the cleavage or bedding

plane with a pneumatic hammer drill

for insertion of explosive charge. |

MINING THE SLATE

The following description of Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

slate mining methods, evolved through

several generations, gives a clear idea of

the standard practice adopted and followed

to-day in Festiniog [Ffestiniog], and was written by Mr.

E. Andrewes, A.M.Inst.C.E., for The

Sheffield University Mining Magazine.

" The normal process of opening up

and working one of the veins has been as

follows. Access is first obtained by means

of an adit level which, if circumstances

permit, would in the first instance be

driven under the overlying hard of the vein.

Otherwise it will be driven to reach the

hard and then continued as a drift along it.

From this level chambers are opened in an

upward direction, at appropriate intervals

under the hard. To appreciate fully the

process of opening and working the chambers,

it is necessary first to detail some

features of the slate rock. That essential

feature, the cleavage, approximately

coincides in strike with the bedding of the

slate, but has a somewhat steeper dip, so

that the cleavage planes cut the hard at a

slight angle. An equally constant feature of

the Festiniog [Ffestiniog] slate beds is what is known as

the ' pleriad ' or ' pillaring.' This

consists in a tendency in the rock to rend

with comparative readiness and regularity

along a plane at right angles to the

cleavage and with vertical dip. The slate is

also cut by frequent joints, which lie at

various angles, but some of the principal of

which, and the most helpful in quarrying

operations, strike and dip approximately at

right-angles to the bedding cleavage. All

these attributes of the slate rock are made

use of in quarrying.

" In opening a chamber, the first

operation is to drive in the slate what is

known as a roofing shaft upwards under the

hard, following the direction of the

pillaring. The roofing shaft having been

driven a certain distance, the next

operation, called widening, is the cutting

out of the top layer of the slate for the

full width of the chamber. The whole process

so far is in the nature of development work,

and is carried on by men classed as miners,

who use some form of dynamite as an

explosive.

" These are now followed by rockmen,

who carry out the actual quarrying

operations, and use gunpowder for charging

the holes. Their function is to quarry the

rock in blocks suitable for working up in

the slate mills, with as little waste and

injury to the good rock as possible. They

must begin by working a ' free side ' to the

rock. This is done by cutting a vertical

slice on the right-hand side of the chamber,

unless some natural feature of the rock

offers an advantageous opportunity of doing

it elsewhere. Having achieved a free side,

it is necessary also to obtain a free end to

the rock before a block can be quarried.

Convenient joints may supply this, but as a

rule a certain amount of cutting away of

rock, in the -form of a trench traversing

the width of the chamber, has to be done.

Where the rock is ' large ' (i.e., has no

joints) near the foot of a chamber, a

channeller is used for cutting free bottom.

" The quarrying of a block can now

be commenced. This is accomplished by

driving a splitting hole along the cleavage,

and a pillaring hole at right-angles to it,

and firing them in turn with a suitable

charge of gunpowder. The holes are placed

about half-way between the free bottom and

the next joint. The latter may be anything

from a couple of feet to twenty feet or more

from the free bottom, but a single hole

properly charged will ' run ' for the whole

of such a distance, and if the cleavage and

pillaring are good, very clean and regular

blocks are produced. It will be readily

understood that there is scope for a

considerable degree of skill and judgment on

the part of the rockman in placing and

charging his holes.

" When one chamber has been worked

far enough forward to clear the level, the

latter is driven further forward and another

chamber started in due course. The distance

normally allowed, measuring at right-angles

to the line of pillaring, for a chamber and

pillar is 85 ft. Of this width, 45 ft. would

be chamber and 40 ft. pillar. But in actual

practice there is a good deal of variation,

which may be due either to the roof not

being solid enough to permit of a chamber

being opened to the full width of 45 ft. or

to a fault or other irregularity in the

ground making it inadvisable to open a

chamber in a certain position.

" We have so far dealt with the

opening and working of a single level or

floor only, but as soon as such a floor is

fairly launched and has a chamber or two at

work, steps would be taken to open a floor

below it. This, in the initial stage of

development of a quarry, was sometimes done

by driving another adit level from the

surface, but the days are long past when

such a course was feasible, and the new

level has to be reached by sinking.

" The method adopted has been to

sink an incline shaft under the chert

overlying the Narrow Vein. A floor is then

opened on the new level in the same manner

as described above, care being taken that

the chambers on this floor line up with

those above. The process is continued

downward on succeeding floors, the final

result being, as regards any particular

chamber that, where conditions permit, the

whole of the slate rock is removed, and it

becomes one continuous excavation from floor

to floor. The quarry, in fact, becomes a

series of alternate chambers and pillars, or

walls.

" Where more than one slate vein is

worked in the same area, the work goes on

simultaneously in each vein, the walls and

chambers in each vein being kept in

alignment and superimposed. This, of course,

entails careful surveying, but is a very

essential feature of sound working. All the

principal slate mines in Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

have

suffered to some extent from falls (subsidences

on a large scale), which in some cases have

had disastrous results as regards the future

working of the quarries. These falls have

been caused chiefly by careless and

unsystematic working in past years. Chambers

have been made too wide, where profitable

slate was to be found, and pillars in some

cases well-nigh obliterated. The stability

of the ground has further often been

adversely affected by total lack of care as

to the placing of the chambers and pillars

in one vein vertically above and in

alignment with those in a vein above or

below it."

|

| A 20-ton block of solid

slate rock. |

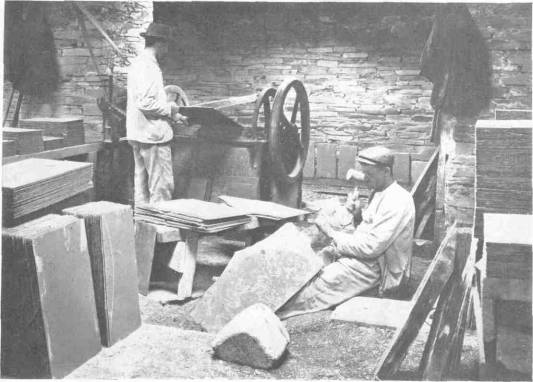

The slate blocks won in the rough are

next hauled to the surface, often by

electric or mechanical traction on the flat,

and up the inclined haulages, whence they

are transported similarly to the mills, and,

after being first split into convenient

slabs, usually 3 to 4 ins. thick, are placed

on circular saw tables where they are

reduced to dimensions suitable for

man-handling by the splitter. Having been

split to the appropriate thickness for

roofing purposes, the still unshaped slate

is passed to the " dresser," who

puts it though a power-driven revolving

knife dressing machine, from which it

emerges in the true rectangular form so well

known to the trade and public, and

characteristic of English roofing slate

practice. Variations in size are obtained by

means of a graduated gauge on the dressing

machine.

Slate mining and production is thus seen

to be a most highly-skilled occupation, with

a special technique of its own, and one

which is largely hereditary, being carried

on by generations of slate quarrvmen, who

grow up with the instinctive " knack

" or " flair " which no mere

training can give, nor machines reproduce ;

an outstanding example of real

craftsmanship.

|

| A splitter and dresser

at work. |

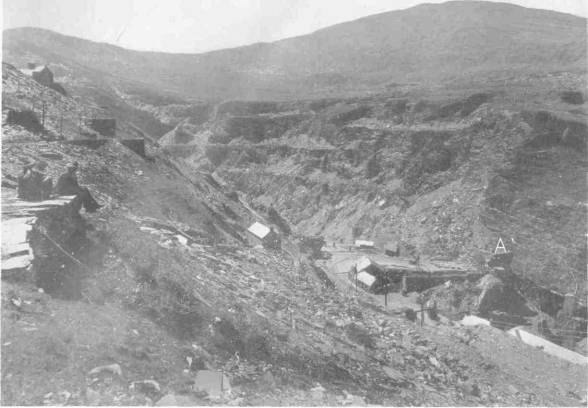

|

| Bird's-eye view of a Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

slate quarry showing old

surface workings, and main entrance to

mine at A. |

Festiniog [Ffestiniog] slate, by reason of its light

weight, unique qualities and high

non-conductivity, has found its way to all

parts of the globe-Iceland, Russia, South

and East Africa, Nigeria, South America,

Australia and New Zealand, to mention but a

few-while on the Continent many important

buildings are roofed with it, notably the

Hotel de Ville at Brussels, Hamburg

Cathedral, and Peace Palace at The Hague.

Apart from the manufacture of roofing

slates, slate is widely used for billiard

table beds, monumental purposes, brewery

tanks, aquariums, electric switch panels,

flat slate roofs (common in America) and

pavements, and even for " honing "

razors, slate giving the finest cutting edge

possible, while three years ago a secret

process was discovered and patented by

members of the Festiniog [Ffestiniog] group, as a result

of long research, by means of which slates

can be treated most satisfactorily by a

colouring process, by which the most

delightful pastel shades, hitherto

unobtainable in any roofing material, may be

obtained. Exotic tints such as peacock blues

and greens, are also available ; in fact,

they can be coloured or tinted to suit each

architect's or user's individual taste, in a

single colour or in any desired combination

of colours and shades. These coloured slates

withstand the action of boiling in acids and

alkalies up to and beyond twice normal

concentration. Mineral, or earth, colours

are alone used and these withstand treating

to very high temperatures. By a chemical

action, definitely beneficial to the slate,

the colour film becomes practically part and

parcel of the slate surface, hardening it

and becoming harder and more permanent with

age.

PRINCIPAL QUARRIES

The principal quarries in the Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

group are the Oakeley-incorporating the Votty

& Bowydd Quarries the Maen Offeren -

incorporating the Rhiwbach-the

Llechwedd (Messrs. J. W. Greaves & Sons,

Ltd.), the Manod and the Craig Ddu Quarries.

Up-to-date machinery, usually electrically

driven, is used. Great care and expense are

involved in keeping workings clear of water,

an important item where the average annual

rainfall varies between 80 and 170 ins.

The slates are entrained at Blaenau Festiniog [Ffestiniog], which centre is served by both the

London, Midland & Scottish and Great

Western Railway Companies, and at Minffordd

Junction (G.W.R.) and shipped coastwise or

abroad at Portmadoc [Porthmadog], whither they

are taken by a wonderfully constructed narrow

gauge railway laid in the early part of last

century on the 2-ft. gauge-at the time the

pioneer of all narrow-gauge railways, on which

was modelled later the Darjeeling railway in

India, and many others.

In conclusion, a good Welsh slate is the

"Rolls Royce" of roofing materials,

and being a natural rock must necessarily be

more lasting than any artificially produced

substitute, however good. It cannot be

mass-produced, nor adulterated, but remains

constant in quality and durability. A genuine Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

slate will easily outlast the

building it covers, and there are many

instances of its re-use on new buildings after

removal from very old buildings on demolition.

While admittedly not as cheap initially as

some artificial " roofers," on the

basis of the real cost of a roof, namely, the

initial cost plus maintenance costs over a

period of sixty years or more, it is "

facile princeps," maintenance costs being

practically negligible, always provided

suitable nails are used. It can be said, with

truth, that the first cost is the last cost,

and now that the only objection to its use,

that of a tendency to drabness- more often

than not caused by a lack of imagination and

suitable architectural design rather than to

any fault of the slate itself-no longer holds good, and

the universal cry for colour and yet more

colour can be aesthetically met, slate should

come, and is coming, once more into its own,

and taking pride of place as of yore.

|

| A length of solid slate

opened out into many laminae, thus

showing the extreme resiliency of this

material. |

OUTPUT OF SLATES. While slates are sold by

number and covering capacity their output is

usually expressed in tons, and to give some

idea of this, the present output of Festiniog [Ffestiniog]

slate is round about 40,000 tons per annum,

equivalent probably to at least 32,000,000

actual slates in the various standard sizes,

24 ins. by 14 ins. to 10 ins. by 6 ins., or

(say) 1,500,000 square yards of slating at 3

in. lap. All British material, produced by

British labour - and it is up to the British

public to insist on having their houses

covered with them to their own and their

children's children's lasting satisfaction.

It is no idle boast that good Welsh slates

are the finest and most lasting roofing

material, but a proved and indubitable fact,

as evidenced on every side and in every part

of the world, for everyone to see for

themselves.

It may be of interest to our readers to

know that in the Festiniog [Ffestiniog] group's largest

slate mine there are more than 30 miles of

tram roads, of which one-half are probably

underground, and it would take a good walker

several days to go through all the workings.

Air pipe-lines run into many miles ; as also

do electric cables. A hearty welcome is also

extended to any who may be in the vicinity of

Blaenau Festiniog [Ffestiniog], in North Wales, near the

centre of Snowdonia, to visit one or other of

the group's slate mines, and to see for

themselves their unique characteristics. We

can promise them an interesting and highly

instructive time, and a unique experience, for

they are to be counted among the modern

wonders of the world, the slate chambers being

easily the largest individual openings to be

found in any type of mining.

|

| A circular saw table at work. |

Printed by LOXLEY BROTHERS LIMITED, 50,

Southwark Bridge Road, London

Source: Reprinted from the Building

Times, 1936.

|