Pay, Strikes and Living Conditions -

Strikes

Early Strikes

Up to

1824 strikes were illegal. It is an interesting coincidence

that not only were the quarrymen at

Penrhyn, Bethesda, on strike during

January, 1825, but that the quarrymen at

Dinorwig, Llanberis,

also struck to

be allowed to finish work at 1.00 p.m. on Saturday rather than at

4.00 p.m. Assheton Smith agreed to this, but Col. Edward Douglas

Pennant refused to negotiate anything. Others followed this first

strike at Penrhyn, one in 1846, which turned out to be a complete

farce, and another one in 1852. Pennant trampled on such actions

with an effective policy of victimisation. Indeed, that would be

the response at Penrhyn for the rest of the century, a response

that culminated in the Great Strike of 1900-03, the longest

industrial dispute ever to happen in the countries of

Britain. Up to

1824 strikes were illegal. It is an interesting coincidence

that not only were the quarrymen at

Penrhyn, Bethesda, on strike during

January, 1825, but that the quarrymen at

Dinorwig, Llanberis,

also struck to

be allowed to finish work at 1.00 p.m. on Saturday rather than at

4.00 p.m. Assheton Smith agreed to this, but Col. Edward Douglas

Pennant refused to negotiate anything. Others followed this first

strike at Penrhyn, one in 1846, which turned out to be a complete

farce, and another one in 1852. Pennant trampled on such actions

with an effective policy of victimisation. Indeed, that would be

the response at Penrhyn for the rest of the century, a response

that culminated in the Great Strike of 1900-03, the longest

industrial dispute ever to happen in the countries of

Britain.

In brief, there was substantial discontent with conditions in

many of the larger quarries, with the bargain system becoming a

disruptive force. Even though the quarries were isolated, the men

could still read about English disputes and trade unionism in

such papers as Yr Herald Cymraeg or Baner ac Amserau Cymru. In

1859-60, builders in London went on strike for a nine hour day,

and the employers replied with an attempt to force workers to

sign a written guarantee that they would not belong to any

society that interfered in any way at all with arrangements made

between an employer and his workmen.

A committee was set up at Penrhyn in 1865 by six men, with W.J. Parry, who was to exert a very

considerable influence on the growth of trade unionism from that

date until 1893, acting as their interpreter. Concessions were

granted and this prompted the men to form a union. They asked Parry

to draw up a plan. 1,800 workers joined at once. Quarry owners

everywhere were alarmed. Five months later, Pennant, who

would be raised to the peerage the following year, stated that

he regarded such an action as a device to estrange him from his

workers and to foster ill feeling between them. He further

cautioned the men, that any attempt to force the issue would lead

to an immediate closure of the quarry, which would only be

re-opened to men who declared themselves opposed to any such

union.

Three days before Christmas, 1,229 quarrymen replied that

their committee was not made up of agitators, but of delegates

elected by themselves, and that they had totally renounced the

idea of setting up a trade union. But they had at least increased

their monthly salary. Of the six men who had formed the original

committee, only Robert Parry was working at the quarry by

1870.

The storm of 1874 breaks.

Unexpectedly, the storm did not break at either Penrhyn or

Dinorwig, but at Glynrhonwy Quarry, Llanberis, where the men

stood firm and refused to disown the N.W.Q.U (North Wales

Quarrymen's Union). Unrest spread to Dinorwig where 11 men

disowned the Union and 2,200 stood by it. The lock out was to

last five weeks, with meetings held at Craig yr Undeb near to Pen

Llyn. The men stayed resolute and achieved a substantial, if not

complete victory. Excitement spread to Penrhyn. The issues were

complicated, but the final threat came from Lord Penrhyn, who

forbad the collecting of funds on threat of closing the quarry.

The battle was bitterly fought and widely publicised, and most of

the demands were met in the Pennant Lloyd Agreement, which was to

remain in force until 1885. However, the management decided to

ignore conditions laid out in the agreement, and the men walked

out again. Consequently, a minimum standard wage had been

achieved and a hated management clique swept out of office. Perhaps most important of all, a committee of men had been

recognised to negotiate on their behalf. Victory had been won

against one of the richest and most powerful men in the realm,

who had set out initially to destroy the union. They were heady

days, and union membership soared. But they were heady days for

the slate industry in general as the profits and dividends of the

Dorothea Quarry from 1870-78 show

|

Profits |

Dividends |

1870

1871

1872

1873

1874

1875

1876

1877

1878 |

£4,678

£4,485

£5,560

£8,769

£10,553

£14,738

£10,718

£10,882

£11,439 |

£6,000

£6,000

£6,000

£6,000

£8,000

£10,000

£16,000

£12,000

£6,000 |

The Dinorwig Strike of 1885-86

By May 1878, Union membership had peaked at 8,368, but in his

address to the annual union conference in 1878, W.J. Parry warned

against a possible downturn in trade and the resulting fall in

wages. He was right. Prolonged depression was setting in. Men at

many quarries struck against the reductions when they came but

just had to accept the worsening situation. It was a situation

that also affected the fortunes of the Union itself. Politically,

George Sholto Douglas Pennant lost his parliamentary seat in the

General Election of 1880, and in his parting address charged the

Caernarfonshire workers with being foremost in falsehood. From

the newspaper reports, one gathers that the result was

unexpected and the magnitude of the defeat immense. After all,

the heir to the Penrhyn had been defeated by more than 1,100

votes. And this, even though G.W.D Assheton Smith had refused to

allow any canvassing at all to take part at his Dinorwig Quarry.

Interestingly enough, was the fact that quarrymen there who

supported the Conservative party were rewarded by a monthly bonus

of £1.00, otherwise known as Punt y Gynffon.

If both he and his father had stood on one of the turrets of Penrhyn Castle looking towards Bethesda, they could see in front

of them a quarry, where the workers spoke a different language to

them, and workers who worshipped in Nonconformist Chapels. Additionally,

the workers

knew more about the quarry and its workings than they ever could

hope to, and since 1874, the workmen, in their eyes, were able to

come and go as they pleased. Workers, who by even 1864, had

supported a local Welsh language press that had sustained the

publication over 170 volumes.

But it was at Dinorwig that the next flare up happened.

Conditions were rapidly getting worse there on many accounts.

Fifty-three men were suspended from working because ten men had

broken a local rule. A mass meeting was held at Craig yr Undeb

where votes of no confidence were passed in the manager, John

Davies, as well as the chief manager, Walter Warwick Vivian,

(b.1856). W.W. Vivian was the son of the second Lord Vivian of Plas Gwyn, Pentraeth,

whose cousin was married to Louisa Alice, G.W.D. Assheton Smith's

sister. W.W.Vivian lived at Glyn, Bangor, and his wife was a lady

in waiting to Princess Mary of Teck. Vivian retired in 1902 and

inherited £70,000 on the death of his related employer. A very

cozy, little family. However, like his counterpart at Penrhyn, Emilius Alexander Young (1860-1910), Vivian had no experience of the quarrying industry.

Both had their training in the hard world of business, and

were not in the least sympathetic to inefficient customs and

practices. During the 1885-86 strike, there is no doubt that it

was Vivian who was in charge at Dinorwig. This is reflected by the fact that on some O.S. maps of the time, the quarry is named

'Vivian's Quarry.'

A deputation was elected to visit G.W.D. Assheton Smith, but his

response was to inform his workforce to remove their work tools

and barics [barracks] furniture out by the last day of October. (After all,

blood is thicker than water!) The lock out lasted until Saint

David's Day, 1886.

Storms gather in the Ogwen Valley

Trade improved in 1890 and 1891, with the

profits at Penrhyn rising from £45,000 to £55,000. They were to

increase to £89,871 in 1892, and wages were increased by 5% in

April 1893. The years 1891-95 also saw a drop in union membership

from 5,970 to 1,423. Ironically, it was the 1896 Labour Day, held

at Blaenau Ffestiniog that was responsible for lighting the fuse

at Penrhyn. Around three weeks before the event, E.A.Young was

informed of the men's desire to attend the festival by an elected

deputation. He refused to meet them, saying that anybody who

wished to attend had to apply for permission individually.

Another deputation informed Young that the men were going to

Blaenau Ffestiniog in a body. On May 1st, he wrote to his master,

Lord Penrhyn, that in his opinion union leaders at Caernarfon had

ordered the Penrhyn men to try and pick a quarrel, with the

ultimate view of re-establishing the Union and the Quarry

Committee as in the days of the Pennant Lloyd Agreement, which of

course had been suspended in 1885.

On May 4th, when around 1,500 of the workforce were absent,

Young closed the quarry in order to throw the loss of wages on

the backs of the Agitators. And to rub salt into the wounds, the

men who had absented themselves from the quarry on May 4th were

all suspended for two days, not for going to the Labour Day Rally

but for being absent without leave. E.A. Young was preparing for

a pitched battle. July and August saw the drawing of battle lines.

On July 2nd, a standard daily wage was asked for and refused. On

August 7th, a list of complaints were sent straight to Lord Penrhyn and apparently bypassing Young. A deputation met him ten

days later, when all the requests were refused. The Penrhyn-Young

axis was as firm as ever, with both singing in perfect unison

from the same song sheet.

Feelings were running high and Young told W.W. Vivian, his

counterpart at Dinorwig, that he would "...stick fast to discipline

and retain the management of the Quarry in my hands come what

may."

Two men were suspended for measuring bargains with a tape

measure on September 15th in order to supply the committee with

accurate information. After failing to present themselves at the

quarry office, where they had been summoned eleven days later,

they were dismissed. At a meeting of the General Committee it was

resolved that in the light of these dismissals, all negotiations

would be terminated and to call a Strike in March, 1896. Two days

later, Young suspended 71 men - the members of the committee and

the seven who had signed the list of complaints

sent to Lord Penrhyn on August 7th.

The day following the dismissals, the men refused to take

their bargains and start work until they received an explanation

of Young's actions. It was September 29th, and the following day

they were locked out. This lock out, which Young called a strike

was to last until August 1897. During this time E.A. Young became

the focus of great resentment. In order to alleviate the poverty

of the men, the Daily Telegraph, together with concerts and

general subscriptions collected £19,161 for the locked out men.

During the lock out, Young always made certain that spies

employed by him kept a meticulous record of not only what was

said but also who said what. These reports were meticulously

scrutinised by him and indexed for further use. Real anxiety,

uncertainty and fear of victimisation remained. In June

1899, Robert Davies, who had chaired numerous

deputations, to Lord Penrhyn was dismissed. Two months before that,

Young ordered that from then on union payments were not to be

collected at the quarry. The situation was slowly but surely

reaching breaking point.

The 1897 Penrhyn Strike Settlement

The Spy

It appears that the spy employed by Young during the Strike of

1896-97 was one Thomas Ellis. Born at Llandyrnog, Denbighshire in

1851, he appears to have travelled around a lot during the first

fifty years of his life as the 1901 Census shows.

Since only the youngest son was born at Felin Hen, it is fair

to assume that Thomas Ellis's family moved into the area around

1898 when the Strike was over. However, he was rewarded with a

post of Inspector at the Quarry for services rendered. (He worked

again for Young during the Great Strike, being paid off in 1903

when he left the district with his family.)

The men had returned to work in August 1897 without gaining

much, and holding both W.J. Parry (who stopped

working for the Union in 1898) and W.J. Williams partly responsible for their

failure.

Young's policy for the next few months was to dismiss anybody

who happened to be conspicuous in the Union. In June 1899, Robert

Davies of Tregarth, the most experienced and respected union

leader, was dismissed. The general manager then went on to

announce that henceforth, no union dues at all were to be

collected at the quarry. The cauldron began to bubble violently,

and finally boiled over October 26th, 1900, in violence against a

number of contractors. Penrhyn decided to prosecute 26 of his

employees, even before they appeared before the

magistrates.

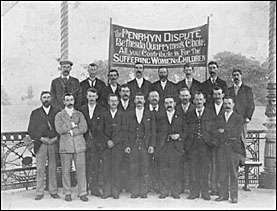

The Great Strike 1900-03

All the men marched to Bangor to

support the 26 at their trial. Everyone was suspended for

fourteen days. The first hearing was adjourned, and the workforce

all marched to Bangor for the second hearing. Of the 26 accused,

only 6 were convicted and fined. The Chief Constable of the

County called in military forces and was condemned by various

public bodies as well as his own County Council. The men went

back to work on November 19th, but 8 galleries were not let out

to be worked. Two days later their suspicions had increased even

more. On November 22nd, everybody turned up at the quarry but no

work was done. Sometime during that fateful morning, E.A. Young telephoned

the quarry with a message to the men to go on working or leave

the quarry quietly. The men walked out. The uneasy truce of

1897-1900 was over. All the men marched to Bangor to

support the 26 at their trial. Everyone was suspended for

fourteen days. The first hearing was adjourned, and the workforce

all marched to Bangor for the second hearing. Of the 26 accused,

only 6 were convicted and fined. The Chief Constable of the

County called in military forces and was condemned by various

public bodies as well as his own County Council. The men went

back to work on November 19th, but 8 galleries were not let out

to be worked. Two days later their suspicions had increased even

more. On November 22nd, everybody turned up at the quarry but no

work was done. Sometime during that fateful morning, E.A. Young telephoned

the quarry with a message to the men to go on working or leave

the quarry quietly. The men walked out. The uneasy truce of

1897-1900 was over.

The Great Strike of 1900-03 had started. Things would never be the same again.

Smaller strikes occurred at Blaenau Ffestiniog in the

following decades, like the Haulers' Strike in 1920, when a

number of the boys who followed the horses at Llechwedd and the

Oakeley came out in August 1920 for an increase in pay. And the

Two pence Strike or Woodbine Strike of 1936. (Assuming that a

packet of Woodbines cost two pence in those days.)

But it was in 1922, the year that it amalgamated with the

T.G.W.U., that the N.W.Q.U. for the first and only time called all

their members out on strike, even though it was only for two

weeks.

There is no doubt that the 1985-86 conflict at Blaenau

Ffestiniog was the largest in recent times. For a start, it was

the longest strike at Blaenau Ffestiniog since 1893. Centered on

the quarries owned by the Ffestiniog Slate Company - Gloddfa

Ganol, Oakeley and Cwt y Bugail, it lasted for seven months.

Founded in 1971, the company had worked a

Bonus System with success for over a decade. But in 1985, the owners decided to

remove this system, as well as continuing to pay women workers on

a lower scale than men. The new system meant a weekly reduction

on average of £28.50. Seventeen workers opposed the new system

and they were dismissed.

It is not easy to define the role of women in the earlier

strikes, but there is no doubt to the part they played during

this dispute. During the Miners' Strike of 1984-85 the women had

been instrumental in sending food parcels by the score down to

the miners of southern Wales. Now, the miners' wives were

reciprocating in kind to the strikers' families at Blaenau Ffestiniog. Incredible support was given to the strike by

institutions and individuals and nearly a thousand letters of

support were received. Added to this were the weekly Saturday

morning street collections undertaken at Bangor, Caernarfon,

Aberystwyth and Cardiff.

Within thirteen weeks, eight men and one woman returned to

work, an act that put an end to a speedy resolution of the

dispute. The name 'Bradwr' [traitor] appeared again in the local vocabulary.

The women also came out on the picket lines in support.

By November, one problem was how to give the 55 children

embroiled in the dispute as happy a Christmas as possible.

Following an appeal, money, toys and hampers flowed into Blaenau

from all over the country, especially so from the mining

communities.

By mid January 1986, the T. &. G.W.U. was heavily

involved, with senior officials appearing on the picket lines. A

cassette, 'Safwn gyda'n gilydd' was produced with some of the

country's chief performers taking part.

'Safwn gyda'n gilydd' Standing

together.

We're not asking for charity or favours either,

What we ask for are our dues for a day's work!

For the sake of those who were sacrificed to the dust of the

blue slate,

For the sake of those who struggled on the rock, the soil and

the face.

We'll stand together - stand together as one.

Another week goes by without a payslip,

We must stand on the picket line and live off fresh air,

We mustn't be fainthearted or break under the strain -

From the arms of faithful friends comes the strength to carry

on.

We'll stand together - stand together as one.

|

A rally of over 2,000 supporters was held on Saint David's

day, 1986 in witheringly cold weather.

And then the end came. In mid-March it was decided to end the

Strike and accept an ex Gracia payment offered to Oakeley

workers. During the same week, another vote was taken, as a result

of uncertainty over the wording of the first proposal. The

original decision was overturned. It was decided to stand out.

But before the end of the week the dispute was concluded.

'The workers are still standing

together, all the workers at Bwlch Quarry have returned to work,

hopefully all at Gloddfa Ganol by Whitsun. The Oakeley Quarry

workers stood together by refusing to be broken up as a team and

let the proprietor pick and choose the workers he wanted back at

random, as it suited him. They decided not to talk to him and now

he is without skilled workers.'

(We stand together, Blaenau Ffestiniog 1985-86

page 67.)

|

|